QE Infinity in Europe, QE4 in another guise in the US. Earlier this month, the European Central Bank (ECB) announced it would take its deposit rate deeper negative – from minus 0.4% to minus 0.5% -- and resume quantitative easing at a rate of EUR 20 billion a month until shortly before its first interest rate increase. The ways things are going, it is going to be a very long time before we get that rate hike – which means we can pretty much regard this as QE Infinity.

The reason we are getting this is as I had written recently – that the European economy is borderline recessionary again.

Germany’s GDP declined 0.1% q/q in 2Q19. Euro area GDP growth was a weak 0.2% q/q in 2Q19. Meanwhile, the IHS Markit Purchasing Managers’ Index for the region fell to 50.4 in September, down from 51.9 a month earlier, signalling marginal growth. The manufacturing PMI is already deep in contraction territory, and is now dragging down the services PMI.

Meanwhile, the US Federal Reserve will resume balance sheet expansion, but we’re not supposed to call it quantitative easing. We have been instructed to call this “OMO” or “open market operations”.

As a result of a recent spike in demand for cash and overnight lending rates, the Fed said it would consider at its late-October policy meeting renewed expansion of its balance sheet.

Remember the Fed blew its balance sheet up from under $900 billion before the global financial crisis to $4.5 trillion by 2015. It had tried to run down its balance sheet from late-2017. But it got its holdings down to only $3.8 trillion. So, the balance sheet is still more than four times what it was before the GFC. And now, analysts are estimating that the Fed could be adding up to another $180 billion a year to its balance sheet each year from November this year. If they keep this up, the Fed balance sheet will blast past the post-GFC high in less than five years.

Call this whatever you like – OMO or QE – the effect is the same. Among other factors, the liquidity crunch coincided with a large auction of US Treasuries.

So, the suggestion here is the Fed cannot run down its balance sheet without creating a liquidity crunch. Indeed, it has to keep printing money to buy government debt, to finance the deficits.

QE hasn’t worked for the Japanese after nearly two decades, why should it work for the Americans and Europeans? This isn’t very new (anymore). It started late 2008 in the US and it goes much further back, to the early 2000s, to the Bank of Japan, when it was called “ryoteki kinyu kanwa” (量的金融緩和), which means, well, “quantitative easing”.

Not so new, but all very abnormal.

The point of mentioning QE’s Japanese antecedent is that the Japanese have been working at it for nearly two decades now and yet, it has had six recessions since 2001. So, why should markets expect QE to work any better in generating sustainable economic growth in the US or Europe?

The market is unlikely to have missed the link between Japan’s economic sluggishness and its government indebtedness.

The link between high debt to GDP and low economic growth. Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff’s research findings on the links between government debt and slowing GDP growth have been around for a while. The research is pretty well known. For the record, they found that median economic growth rates for countries with government debt over 90 percent of GDP were about one percent lower than otherwise. The mean growth rates were even lower.

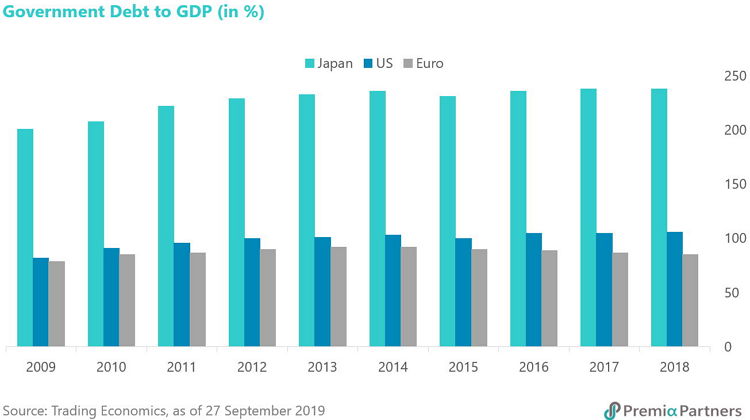

Yet, that level of government debt to GDP is pretty much where we have found ourselves. Running in tandem – and indeed fuelled by QE – has been the rise of government indebtedness around the world since the global financial crisis.

US government debt to GDP has gone from 82% in 2009 to 106% in 2018. In Japan, it has risen from 201% in 2009 to 238% in 2018. Euro Area government debt went from 79% of GDP to 92% in 2014 before easing towards 2018 – largely driven by a decline in German debt. Don’t bother looking for debt consolidation in France, Italy or Spain. Collectively, Euro Area government debt to GDP is still higher than in 2009, at around 85% by end last year.

Why we can’t get out of this money printing and debt dilemma. Conventional economic management would argue that policy makers should stimulate the economy by fiscal and monetary means when activity sags and wind that back when growth picks up. However, the demands of the political cycle in democracies mean that politicians are reluctant to cut back on spending as economies revive, as they are already looking at the next election. So, the political cycles demand continuous attempts to void the economic cycle.

Central bankers are now apparently prisoners of the same paradigm. Indeed, the central bankers’ dilemma is worse. They are now hostage in a fragile monetary edifice they have built. They can’t pull the money out without bringing the house down.

Resource allocation distortions and asset bubbles. Then there is the problem of QE’s impact on asset markets and resource allocation.

By the Fed’s own admission, QE works by raising asset prices and hence lowering yields. All of that is supposed to encourage spending (the wealth effect) and investment (through lower cost of funds).

The problem of course is that only the wealthier segments of society have had portfolios to benefit from the so-called “portfolio balance channel”. The poorer segments of society are merely “hostages” to those who demand QE – that is, “hostages” to the argument that if central banks don’t deliver QE, the most vulnerable in society will lose their jobs. But as home prices rise along with those of other assets, the most vulnerable in society cannot even get into home ownership. In the process, wealth inequality grows.

Beyond that, QE and other forms of perpetual stimulus also work to distort resource allocation, creating bubbles. They drive down the discount rate for net present value calculations, hence pushing up asset prices.

Fast forward a decade or so since the start of QE in the developed world ex-Japan, we now have $17 trillion in negative yielding debt, more than a quarter of the total value of the world’s outstanding debt. The rate at which that segment of the bond market has been growing is breathtaking – it has doubled since the start of the year.

You don’t have to look very far if you are looking for a bubble that can spark another financial crisis. This is another illustration of how central banks are now captive in the house of cards they have built. If rates go up significantly, that house comes down on them.

So, what can they do when the next recession hits? Well, the European Central Bank has given us some insights, as the Euro Area economy teeters on the brink.

Historically, it has taken some 500 basis points of interest rate cuts to pull the US economy out of recession. The Fed doesn’t have 500 basis points of rates to cut. Then what about the Europeans and Japanese, who are already on negative rates? Well, they will do more of the same – fire up the printing presses and take rates deeper negative.

Debt is already weighing on growth and deeper negative interest rates could worsen the situation. Recent research by Princeton University economists Markus Brunnermeier and Yann Koby suggests that ultra-low interest rates eventually trigger a “reversal” of its intended effect on the economy by damaging banks’ profitability and capital, hence limiting their ability and willingness to lend. They called the point at which “accommodative” monetary policy starts having a contractionary impact on the economy the “reversal rate”. And there’s another twist to this: QE increases that “reversal rate”, they warn. So, with QE, the benefits of lower interest rates “reverse” much earlier than without QE.

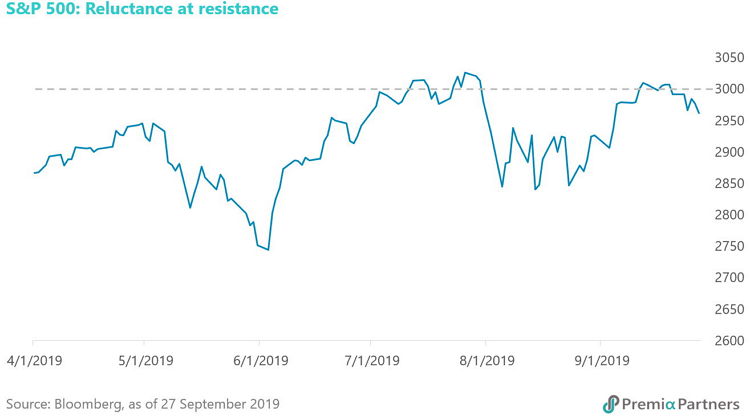

Back to the markets – why investors are thinking 3 or 4 times about storming the 3028 peak on the S&P 500. Investors don’t have to be Princeton University economists to work out that this is dangerous stuff they are dealing with – hence their reticence to break new highs. They might eventually be forced by policy makers into yet another roll of the dice but they will be increasingly jittery. They are not oblivious to the risks.

Firstly, their net present value calculators “go on strike” with negative rates. How do they decide what to pay for an asset? Infinity is surely not an option, even in these abnormal times?

On the economic front, lower rates may actually harm the economy and QE can force higher the point at which harm occurs.

Then the extreme uncertainties brought about by QE and negative rates may cause people to save more, not less.

But let’s suppose negative rates eventually force people out of savings. What then? Nobody bothers to save, everybody borrows and spends with abandon, and governments fund their deficits with debts they can never repay? The defenders of unconventional monetary policies will say this is extreme fear mongering because central banks will reverse those policies long before that happens. Really? Like they are (not) doing now?

To see the previous article from Say Boon: Navigating Turbulence – Six Strategies