Fed bond buying won’t prevent the coming wave of debt defaults. Although the US Federal Reserve has brought down corporate credit spreads, it is unlikely to stop a coming wave of defaults.

It brought down spreads because it bought up debt in the primary market, through exchange traded funds and directly on secondary markets.

Yes, the tightening of credit spreads will reduce funding stress, allowing companies to issue more debt to meet payments they might not have otherwise been able to make. But that is akin to being allowed to borrow more on a new credit card at a lower cost of funds to pay demands from other credit cards. It doesn’t solve the underlying problem of a sudden shock to cash flow, or solvency.

This may have been missed in the midst of the stock market’s bullishness – debt defaults have already been surging. According to Fitch Ratings, the year to date default volume surged to USD 36.9 billion from USD 14.6 billion in May. Fitch is expecting USD 80 billion by year end, surpassing the previous high of USD 78 billion recorded in 2008.

In some sectors, the default rate will likely reach catastrophic levels. Fitch reckons 18% for US energy and 19% for retail companies by end of this year, and 40% for leisure/entertainment by year-end 2021. This is from Fitch’s universe of rated credits and there’s a very good chance that the unrated sector – which will have many more SME companies – will see even more defaults.

So, despite the cheery demeanor of stock market indices and credit spreads, the Fed has clearly not prevented an acceleration of defaults. Note that we are only five months into the pandemic, and we are starting to see rollbacks in the easing of restrictions in the US.

Welcome to Zombie Land. Deutsche Bank Global Research recently estimated that nearly 20% of US companies are “zombies” – with interest coverage ratios of less than one. Among the smaller companies, the situation is more dire. According to the Wall Street Journal, 42% of Russell 2000 companies are losing money. It is only a shade below the 2009 peak of 44% and we have yet to see the peak of the credit fallout from this pandemic.

Here’s a peek at what is lying ahead. According to S&P Global, the three-month rolling downgrade count of loan facilities in the S&P/LSTA Leveraged Loan Index outpaced the rate of upgrades by a ratio of 43 to 1 in May.

This is important because downgrades typically forewarn of coming defaults.

So, that’s a staggering figure, considering that during the Global Financial Crisis of 2008-2009, the three-month rolling count of downgrades versus upgrades peaked at just 8.45x. So, to take this literally, this is already 5 times worse than the peak of the GFC.

How does the Fed’s USD 750 billion bond buying programme measure up to the job? The US Treasury has seeded the USD 750 billion fund earmarked for buying corporate bonds and corporate credit ETFs with USD 75 billion to absorb losses that might occur from that bond buying program.

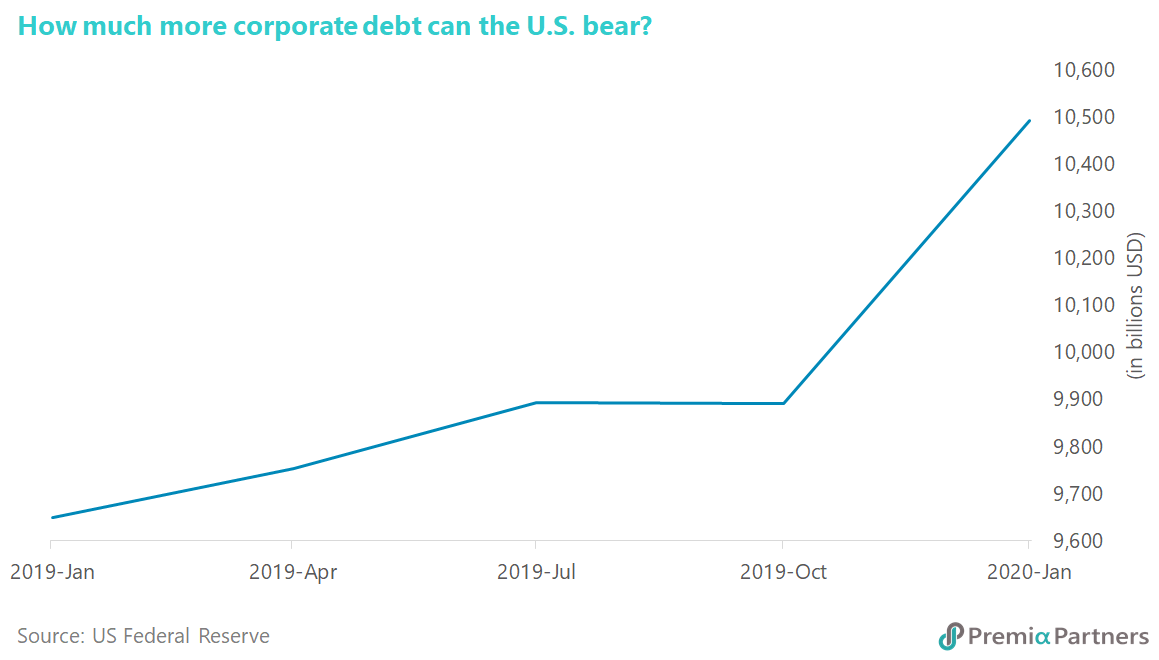

That’s a lot of money. Note that as at end-March, there was already USD 10.5 trillion (repeat trillion) in non-financial corporate debt in the US. Meanwhile, the rate of new issuance is running at more than double the same time last year.(Figure 1)

Sure, the Fed can always ask for more loss absorbing capital from the US Treasury to buy more debt. If the US Treasury needs more funds, it can issue more UST bills for the Fed to buy.

Yet, the Fed is already facing growing criticism for “nationalising US capital markets”, and “rigging” the markets through its control of both the price and volume of money. Meanwhile, if the Fed “goes for broke” (pardon the expression) on monetary expansion, Dollar decline could become disorderly, triggering instability in the global financial system.

Bottomline: The Fed will continue to suppress credit spreads to give financially troubled companies room to refinance. It might even bail out systemically important companies and the largest US employers. However, it is unlikely to take on the cost of keeping alive every corporate “zombie” that shows up at its doors. Don’t overstay the credit rally.