China’s youth unemployment rate has been much talked about but poorly understood, with the media mostly missing legacy, structural, transformational and societal factors which would give the market a different understanding of the phenomenon.

In fact, recently a Peking University professor even flagged an eye popping number of 46.5%. This outsized figure came about by adding youngsters who were "not in employment, education or training" (NEET) and also not actively looking for work – which is not the way youth unemployment is measured in most countries. According to the OECD definition, a country's youth unemployment rate is the ratio of unemployed 15- to 24-year-olds to the overall youth labour force. To qualify as unemployed, one has to be without work but available for work and to have taken active steps to find work in the last four weeks. Using the professor’s approach, many countries’ youth unemployment problem would be worse than in China.

China's official jobless rate for urban youth, released monthly by the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), uses a more or less similar formula, which is in line with the International Labour Organization's statistical standards. It is calculated by dividing the unemployed - people who are jobless but have been actively seeking work in the past three months and can start work in two weeks should they get hired - by the total of employed and unemployed people.

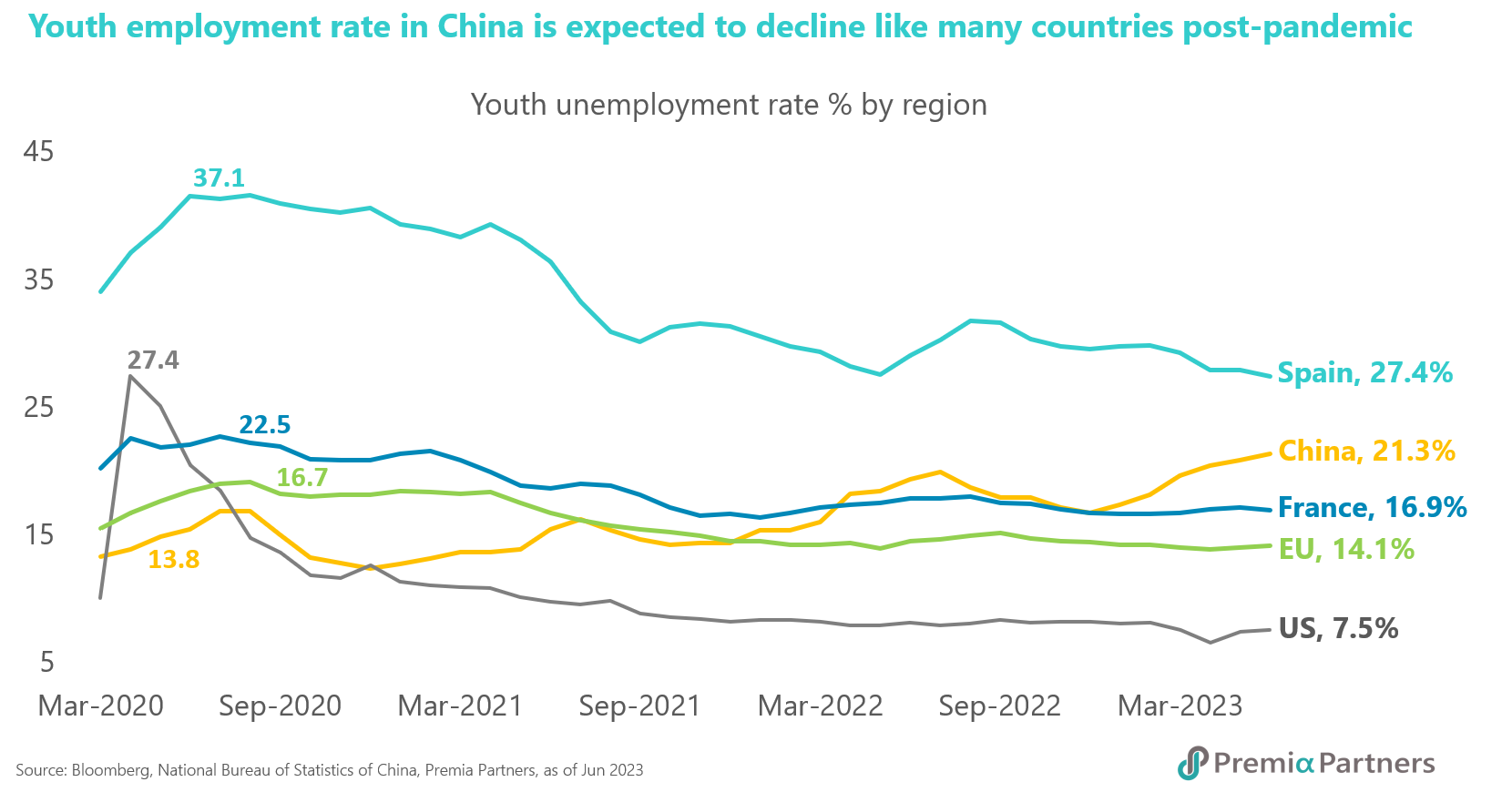

Given China’s relatively late reopening from the COVID-19 pandemic, there is a lag in China’s youth unemployment data compared to western countries. That’s the legacy from COVID-19, which we are confident will pass.

Then there is the quite unique convergence of a number of structural factors which have contributed to the current high youth unemployment figure. These include the expansion of vocational education in 2019, delays in employment due to the three-year pandemic, and the influx of students returning from overseas this year.

There are also economic and societal transformations which have resulted in young people taking time out between completing their education and starting work. That is similar to what young people in the West would call “taking a gap year”. Adding to this, in one-child families, where single offspring enjoys a family safety net, there is a more relaxed attitude towards entering the workforce among Gen-Z Chinese. Indeed, many are compensated by their families to stay at home with their parents, giving rise to the term “full time children” or “professional children”. But even that is likely to also pass as these so-called “full time children” mature.

Another factor is the rise of a rather unique form of self-employment in “companionship” services.

Overlaying all of that, a singular focus on youth unemployment distorts the market’s view of the overall Chinese economy, where urban unemployment for the 25-59 is only 4.1%1, which is lower than where it was before the pandemic.

Without trivialising the situation, this presents a more nuanced appreciation of the phenomenon than the media’s (as usual) wildly pessimistic predictions of social instability and deep economic malaise.

Elevated unemployment rate – a transitory Covid-19 legacy. Many countries have experienced high youth unemployment in the post-pandemic era. For instance, the youth unemployment rate in the United States reached 27%2 for individuals aged 25 in April 2020, while France and Spain peaked at around 22%2 and 37%2 respectively. The MENA region still faces a rate of 25%3 in 2022, and South Asian countries hover around 21%3.

However, looking only at the youth unemployment rates does not give a holistic picture of the economy as a whole.

It is a global phenomenon that unemployment rates are substantially lower for the mature labour segments of the labour force. In China, the urban unemployment rate for individuals aged 25-59 reached a new low of 4.1%1 in June, which is 0.3 percentage points lower than the pre-pandemic rate in 2019.

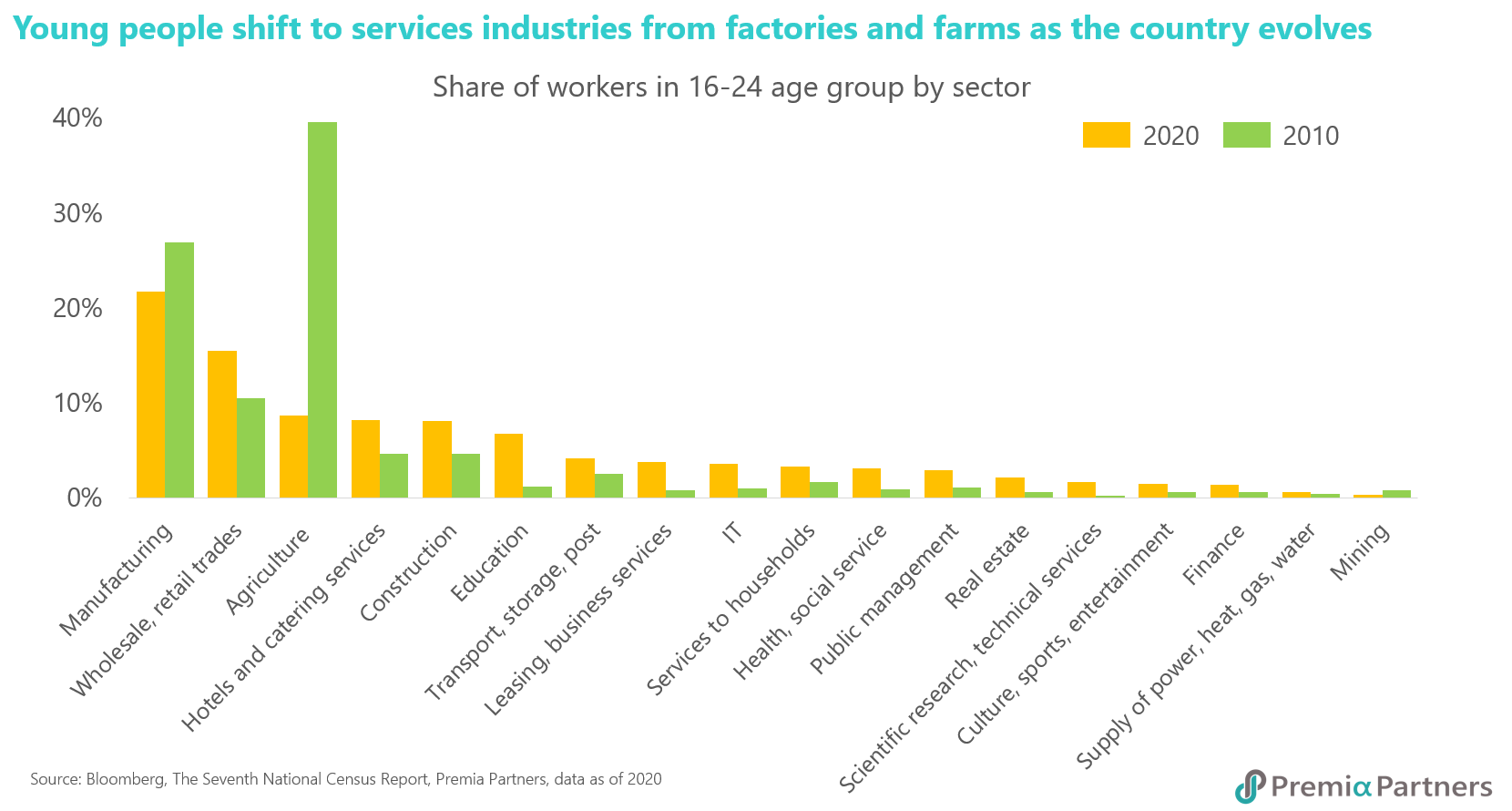

China’s unemployed youth will likely be absorbed into the workforce eventually as the economy continues on its path of recovery, as in other countries. There are structural and systemic factors which can provide a broader understanding of the data. On the supply side, the expansion of vocational education in 2019, delays in employment due to the three-year pandemic, the influx of overseas students returning to China this year, and other unique circumstances during the pandemic have contributed to the high youth unemployment rate. On the demand side, many labour-intensive industries such as export-oriented manufacturing sectors and service industries have deferred recruitment due to the slow recovery post-pandemic. This resulted in a mismatch in supply and demand, leading to structural imbalances. Yet, with China's domestic demand and exports gradually recovering, this portion of graduates who have not yet found jobs will likely see improved employment prospects.

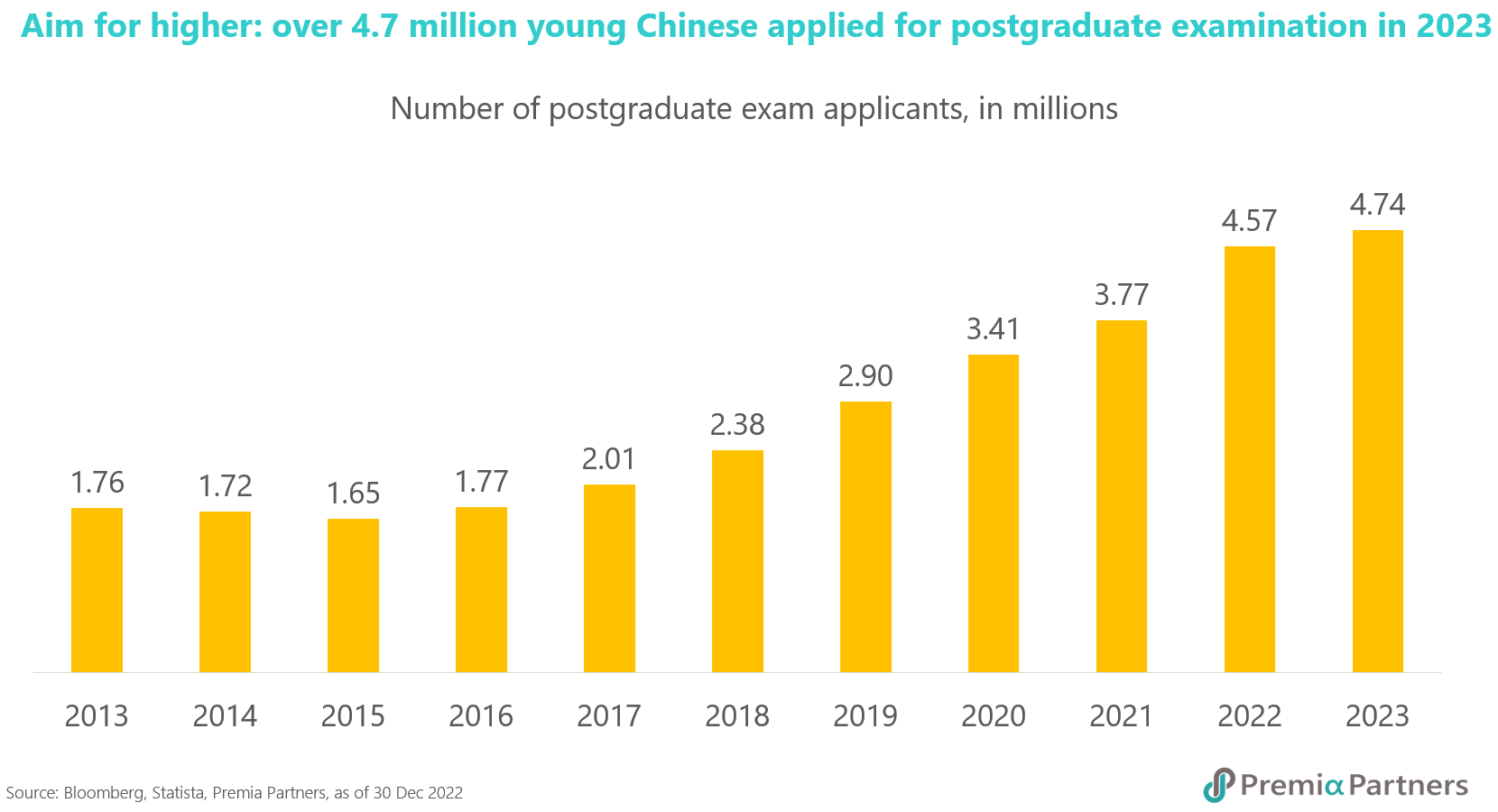

For highly educated graduates, the trend of "slow employment" seems to have become a new trend. Some young people have chosen not to enter the workforce, preferring instead to pursue further education or government examinations. Others are picky about their career choices due to the family safety net they enjoy. According to official data, there were 4.7 million4 candidates registered for the national postgraduate entrance exam in 2023, representing 41% of the total number of graduates. Further, there were 2.5 million5 applicants who had applied for China's National Civil Service Examination, despite a very high recruitment ratio (applicant to hire ratio). Post-pandemic, there has been heightened enthusiasm to pursue further education and to join the civil service. Stability seems to have taken precedence over salary and job opportunities in the priorities of young people following the pandemic. However, we expect a gradual return to the norm – that is, this apparently pandemic-triggered mindset should shift as the economy recovers, even faster than anticipated.

The family safety net provides Gen-Z more flexibility to become “full-time children全职儿女”. After decades of the one child policy, this generation of the young is nothing like the migrant workers of 2008, who were living hand-to-mouth and had to move back to their villages once jobless. Rather, many are the precious single child of the family or families from both the paternal and maternal sides. As the ‘concentrated bet’ of the families, many parents and grandparents understandably are often more ‘risk adverse’, much less willing for their children to go through physical or emotional hardship, and much more ready to lend financial support instead. With their parents' support, they are less anxious to rush into the workforce. There is less urgency to jump at whatever jobs are available. They can live with their parents, be a bit more careful with their money, and take a gap year to figure out what they want to do next in their careers.

This is quite normal in developed economies, and as urban China advances in income, it should not be surprising to see the same social phenomenon in China.

Many would have read reports about the phenomenon of so-called "full time children". They frequently do day trips to the city, hang out at trendy coffee shops, and capture Instagram-worthy photos before returning home to do family chores or look after the elderly. But such indulgences will likely decrease with age, as the “professional children” mature.

The phenomenon of "light work" among young people has led to the emergence of numerous new professions that emphasise interests and hobbies. During the pandemic, with ample online time, there was a surge in roles such as tarot readers, career consultants and companions who provide “psychological value”. Young people, seeking solutions for confusion, anxiety, comfort and psychological healing, have turned to spending on professional guidance or divination. Post pandemic, companionship services have become a popular form of employment and consumption, with an increasing number of young people renting out their leisure time, skills and experiences to make a living. The forms of companionship vary widely, including conversation partners, medical companions, driving companions, travel companions, shopping companions and gaming companions, among others. Reports suggest that by around 2025, the market size of the companionship economy could reach 40 to 50 billion yuan6. Although it is novel, we have to consider this as a new service industry and a legitimate form of self-employment.

Despite proficiency mismatches among highly educated graduates, the government has been making efforts to reduce gaps. Beijing has been pushing state-owned enterprises to hire at least as many graduates this year as they did last year, by giving vocational education and providing training and internship opportunities. For those who cannot land interviews before graduation, universities are formulating pairing and support plans to address mismatches. Besides, China has been granting private companies subsidies including one-time employment subsidies, vocational training subsidies, social insurance subsidies, employment apprenticeship subsidies and other preferential benefits. Many local governments also match local private enterprises with universities and provide tax reductions for high-tech manufacturing and services sectors.

240 million tertiary educated individuals – the workforce transformation from highly educated individuals to high tech professionals. Although the National Bureau of Statistics has suspended the release of youth unemployment rates by age groups, the recent media narrative has oversimplified and misinterpreted the youth unemployment situation. The market has reacted to the negative media by selling Chinese equities. That is, the negative news has been priced in. On the other side of the balance, there are several points that have not been adequately understood and reflected in the market.

According to World Bank data, China's gross enrolment rate in higher education has increased from 26% in 2011 to 64% in 2021 (compared to the global average of 40%)7, thanks to the 12th and 13th Five-Year Plans. As of 2022, China had a population of 240 million8 individuals with tertiary education, and these graduates will serve as a talent reservoir for building the high-tech manufacturing and service industries.

As with many industrialised countries in developed markets, China is currently transforming untapped highly educated individuals into high-tech professionals, as major economic growth drivers evolve, warranting very different factor contributors and skilled talents. The significant number of higher education talents will continue to contribute to China's transition to high-quality development, and this transformation may be achievable in the coming few years. While the process of transitioning labour pool into productive talent pool in this journey will take time, this significant pool of highly educated young labour will provide China with a very important and relevant reserve as the country advances its productivity and evolves towards its goals as a high-tech, modern society with various strategic national goals including its net zero ambition.

The youth unemployment issue is unlikely to persist in the long term. Meanwhile China’s high-tech manufacturing and service industries stand to benefit greatly from the structural transformation underway. The currently deep-valued Premia CSI Caixin China Bedrock Economy ETF (2803), Premia CSI Caixin China New Economy ETF (3173), and Premia China STAR50 ETF (3151) would be especially relevant, as allocation tools which have well captured the opportunity for China's transition to high-quality development and the alpha return along with the economic recovery.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

2 Source: Eurostat, “Unemployment by sex and age (less than 25 years) – monthly data”, 26 August 2023.

7 Source: World Bank, “School enrollment, tertiary (% gross) - World, China”, 24 October 2022.

8 Source: State Council, “More Chinese receive higher education”, 18 May 2022.