Macro Developments and Factor Performance

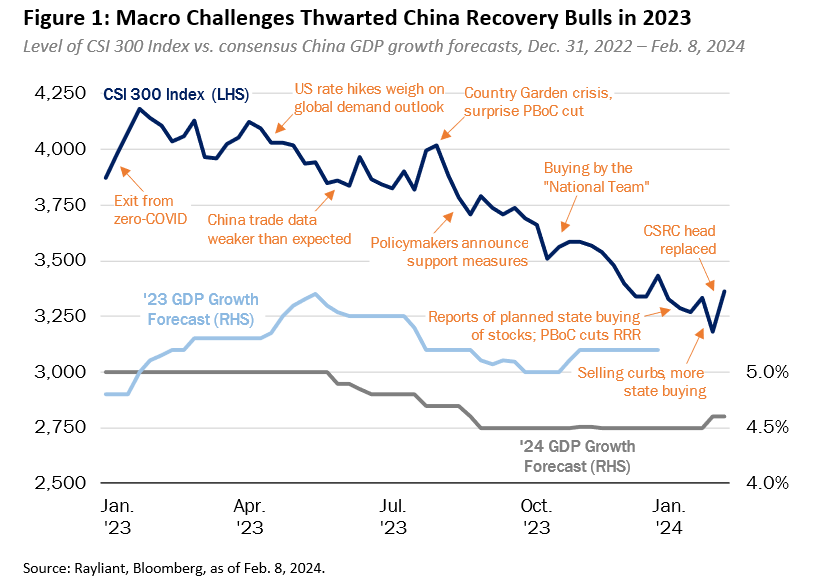

We entered 2023—as, we suspect, did many long-time observers of China’s onshore equity market—feeling cautiously optimistic that after a year languishing under strict pandemic-oriented public health policies, the nation’s abrupt exit from zero-COVID restrictions would put its economy back on track. We hoped that China would enjoy the same reopening wave experienced in other major economies a year prior, with massive pent-up demand and precautionary savings unleashed, catalyzing a return to growth in areas ranging from the blue chip consumer economy, powered by China’s growing middle class, to its rapidly expanding new economy, including firms in strategic areas like semiconductor manufacturing, green energy technology and industrial automation. Alas, such exuberance turned out to be short-lived. By the beginning of the second quarter, new headwinds to China’s recovery had emerged, dragging growth forecasts down and taking equity indices to new lows (see Figure 1).

From the outset of rising excitement over China’s zero-COVID exit, it was clear that any recovery would be at least partially offset by softer expectations for the global economy on anticipated Fed tightening, as what the US central bank initially dismissed as “transitory” inflation became too hot for policymakers to ignore. Those rate hikes began at the end of Q1, inducing a sell-off in emerging markets, generally, and although April brought a surprising surge in exports from China, most economists read through that as an artifact of manufacturers working through a backlog accumulated during China’s mass lockdowns. Those fears were confirmed when May trade data fell far short of consensus forecasts.

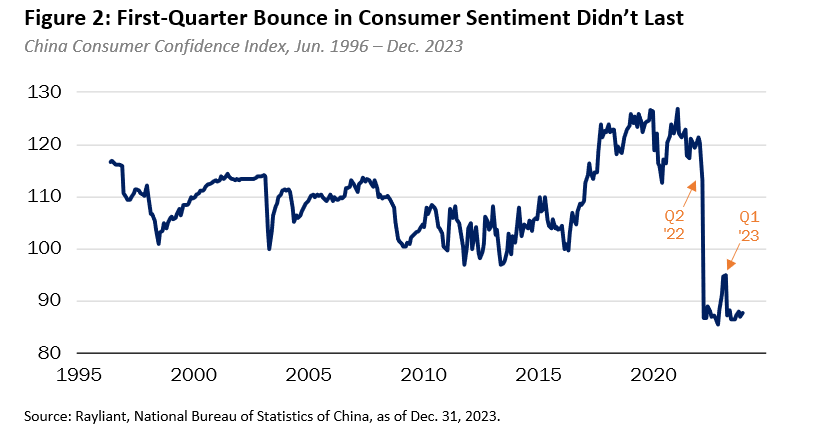

Although it was not surprising to see China’s post-pandemic rebound begin in services—things like restaurants and domestic travel, which were hardest hit by the prior year’s restrictions in mobility—a sustained recovery would require domestic demand to eventually broaden beyond the obvious ‘reopening trade’ sectors, and that clearly was not happening by the second quarter. A weakening global macroeconomic backdrop clearly did not help matters, but readers of our commentary on past quarters will know we see the ultimate culprit behind lack of traction in China’s return to growth as persistently low confidence on the part of consumers and companies. While households felt a Q1 spike in sentiment that mirrored investors’ brief enthusiasm, it did not last (see Figure 2).

Perhaps the greatest obstacle to a rebound in domestic confidence was turmoil in China’s property market. That sector’s woes were nothing new, having begun with the Three Red Lines policy, rolled out in 2020 as a way of deleveraging what authorities perceived to be an over-inflated property market. Those regulations predictably pushed many of the nation’s biggest developers into a liquidity crisis, including China Evergrande—the most valuable real estate company in the world as recently as 2018—which fell into default in 2021 and was recently ordered by a court in Hong Kong to liquidate. Country Garden, another major developer nearly defaulted in Q3 of last year, triggering a fresh wave of panic around China’s real estate market, which spooked investors, but also rattled the nerves of prospective homebuyers and cast a darker cloud over the many industries feeding China’s massive property sector.

For its part, the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) did undertake monetary easing throughout 2023 in an effort to kickstart spending and investing, although a bleak outlook for the global economy and even gloomier prospects in China’s property market meant households and firms had little incentive to borrow, regardless of the availability of liquidity. Meanwhile, supportive statements by policymakers seemed to fall on deaf ears as consumers, companies and investors discounted authorities’ cheap talk, waiting for more substantive fiscal measures as proof the state was putting its weight behind sustained policy stimulus. In the absence of that, even tweaks to financial regulation meant to improve market liquidity and reports of equity purchases by the so-called “National Team”—a collection of state-affiliated entities that has periodically intervened to prop up domestic stocks in times of crisis—were not enough to prevent the CSI 300’s slide into year-end.

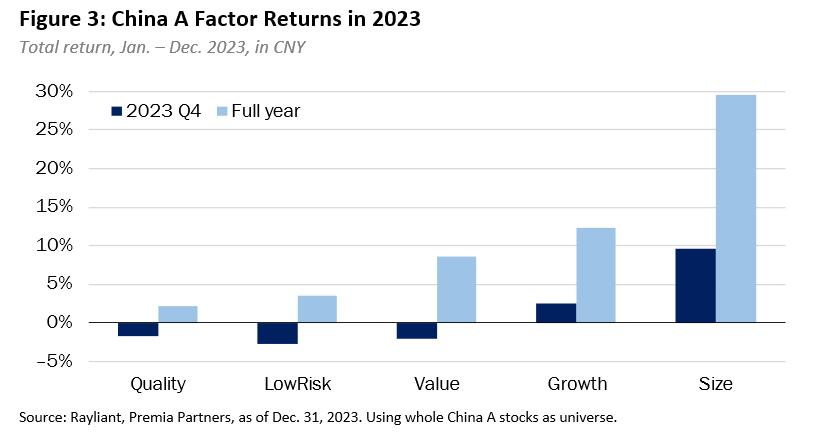

Despite a challenging beta environment last year, there was plenty of factor alpha to be earned, with most major smart beta categories returning positive performance in 2023 (see Figure 3, below). As we remarked the last few quarters, tilts toward stocks with favorable Value and Low Risk characteristics tend to confer their biggest benefits in a broad market downturn, explaining their outperformance for the full year.

Poor performance to Momentum—not depicted in the chart—was similarly unsurprising, as sharp moves in sentiment can cause problems for the trend-following factor. Quality stocks saw modest gains in 2023, with most of the upside in high-quality Growth firms, in part due to enthusiasm around AI and an expectation innovative firms would both hold up better amidst poor macro conditions and also see benefit from state support to strategic technologies. The best returns by far, however, accrued to small cap stocks picked up by the Size factor, as measures to boost liquidity through, for example, reduction in IPO authorizations and a cut to the stamp duty, tend to be amplified in smaller companies’ shares.

Index Performance and Outlook

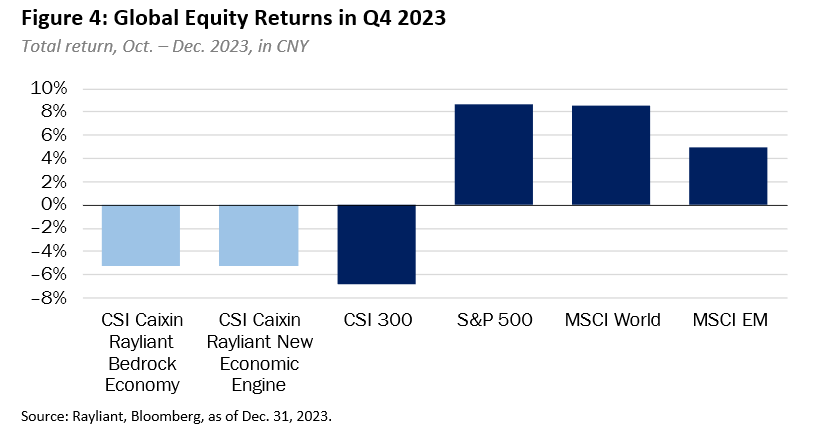

Weak onshore sentiment and the failure of China’s reopening recovery to sustain beyond enthusiasm at the start of the year saw mainland stocks decline again in Q4, with the CSI 300 Index -6.8% (CNY) lower for the quarter (see Figure 4, below), putting the benchmark down -9.1% for the full year. U.S. stocks, by contrast, finished the year with a bang, surging +8.7% in Q4 as strong data on growth and employment raised investors’ hope in a soft landing for the world’s largest economy and prompted the Fed to include a forecast of 2024 rate cuts amidst projections coming out of its December FOMC meeting; U.S. stocks ended the year up an impressive +30%. DM stocks around the world likewise began pricing in monetary easing during Q4, with the MSCI World Index rising +8.5% for the quarter. Even with the decline in Chinese stocks, brightening prospects for the global economy sent the MSCI EM Index to a +5.0% gain in Q4, up +13.4% for the year.

Although broad weakness in Chinese stocks brought down both the CSI Caixin Rayliant New Economic Engine Index (tracked by Premia’s 3173 HK/9173 HK ETFs) and the CSI Caixin Rayliant Bedrock Economy Index (tracked by Premia’s 2803 HK/9803 HK ETFs), which fell by -5.4% and -5.2%, respectively, in Q4, each meaningfully outperformed the CSI 300 Index, which lost -6.8% for the quarter. And while the growth-oriented nature of the new economy index led it to suffer slightly more for the full year than the broader market, returning -9.5% in 2023 versus the CSI 300’s -9.1% return, the bedrock index managed to post strong positive performance for the full year, climbing by +7.7% over the same period and delivering very meaningful alpha vis-à-vis most mainstream passive as well as active China A strategies.

We also observed some investors using Bedrock for risk management and income given its above-average dividend yield, in combination with the New Economy for more measured China exposure to position for recovery opportunities. In addition, the two strategies’ measured exposure to Size was a big tailwind in Q4—more than enough to offset weak Value and Low Risk performance for the quarter in the bedrock index—which largely accounted for the two indices’ outperformance against the CSI 300 over the last three months.

Both strategies benefitted most strongly from selection effects aided by the policy-aligned sector screen, with sector-level bets hurting bedrock at the margin (an overweight to Real Estate and underweight to Consumer Staples were the biggest detractors) and helping the new economy index (a large overweight to Health Care contributed most). This reflected as well that policy-aligned sectors tend to be beneficiaries of government contracts, and thus more stable cash flow, and also stand to see more action from the National Team relative to broad markets.

Admittedly, the commentary thus far has been quite gloomy. That said, developments in the first month of 2024 heading into Chinese New Year have, amidst exceedingly cheap valuations and what looked an awful lot like capitulation on the part of investors at year-end, once again given us reason to hope for a turning point in policymakers’ drive and the market’s confidence.

The far righthand side of Figure 1 shows supportive measures picking up steam at the turn of the calendar year, leading to a jump up in the CSI 300 in January 2024. Thus far, efforts to catalyze a rally have mostly concentrated on injections of liquidity into the stock market, including through tweaks to financial regulations mentioned before, as well as reports of direct intervention to buoy stock prices through purchases by the National Team.

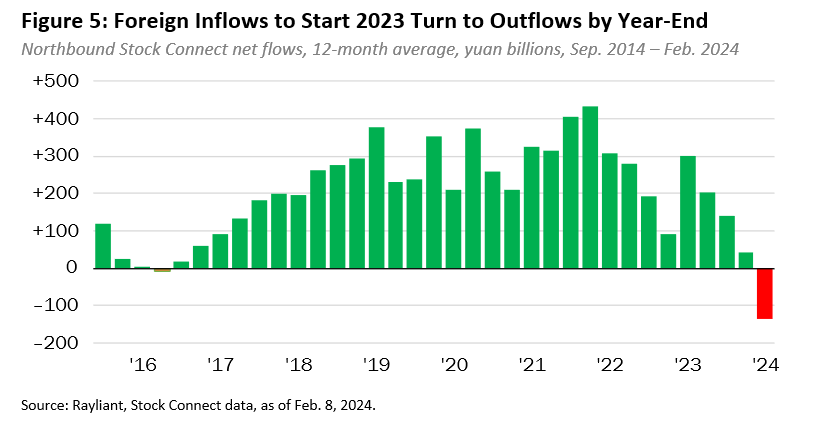

In Figure 5, we plot a moving average of quarterly net flows from foreign investors into mainland A shares as a reminder of both investor optimism toward a rebound in Chinese shares at the beginning of 2023 and the rare outflows at year-end as many gave up hope. That said, according to Goldman Sachs Prime Book data, hedge funds have been net buying Chinese equities in each of the last 3 weeks and 11 of the past 15 trading sessions and year to date Northbound returned to net positive 6.7 billion yuan (~US$1 billion) through the beginning of February. The question, of course, is whether the recent flow back into Chinese equities will be another false start or prelude to a rally when stocks resume trading in the Year of the Dragon?

It is not uncommon for pundits to mention policy lags when discussing the impact of moves by the US Fed, and we note that even though China stimulus has been disappointing thus far, there has been a shift in authorities’ orientation since the July Politburo meeting.

Specifically, as economic activity stagnated, as mentioned above, we have witnessed an obvious escalation in reflationary measures meant to address a struggling housing market and challenged local government financing vehicles. So far, that’s manifested as budget expansion, initiation of local government debt resolution, and easing (albeit at the margins) in the real estate sector. All of that is fine, but it is clearly not been enough, which is why—aside from brief rallies in the wake of interventions focused directly on equity investors—we have not seen anything remotely like a recovery in domestic sentiment.

Searching for clues that might indicate a more meaningful scaling up of support, one event on China’s Q4 calendar we had been awaiting with great interest was the Central Economic Work Conference (CEWC), an important policy meeting that kicked off middle of December. The clear message from that meeting was that economic growth was a top priority—no surprise—but much more importantly, we finally got a very clear acknowledgment that more fiscal support was needed and, at long last, some explicit reference to the need for boosting flagging demand, which we have pointed to as a much bigger problem than liquidity, actually quite ample by this point.

We see these pronouncements as foreshadowing much more significant fiscal stimulus coming through in the year ahead. There will be strong incentive to follow through, given what was revealed at the World Economic Forum to be another “around 5%” GDP target for this year, which becomes much harder to hit without the base effects from a supremely soft 2022 comparison that Beijing enjoyed last year.

The challenge for policymakers in 2024 will be to balance the obvious need for greater support with the party’s desire for shifting to a higher-quality growth, moving beyond less productive manufacturing and real estate as core drivers of China’s economy. While there is clearly a need to do something to fix sentiment in the property market in the short run, our read of the CEWC is that investors should not expect a massive bailout in that sector.

Instead, we believe Beijing will target fiscal support at more strategic sectors that fit with the party’s long-term objective to make China more like Germany: a powerhouse in precision manufacturing, significantly higher up the value chain in production from where the country is today. We believe the nature of this transformation will also naturally favor mainland-listed A shares, since policy support of this kind is much more likely to benefit those companies driving China’s domestic economy.

Extremely negative sentiment toward Chinese stocks building over the last two years, reflected in the preceding section’s fairly dismal appraisal of the nation’s economic situation at the conclusion of last year, have brought A shares to exceedingly low valuations for an economy with so much inherent growth potential. That said, we believe investors will look back at 2024 as a turning point for China’s equity markets, with the path toward a recovery outlined above making this an outstanding entry point.

We see differentiating features of the bedrock and new economy indices—including a focus on mainland shares, factors tilting toward bargain stocks and high-quality growth at a reasonable price, along with a concentration in strategic sectors that truly drive China’s real economy—as making these strategies ideal for capturing what we expect to be a pivotal year for Chinese stocks.

*****************************************************************************************************

Dr. Phillip Wool is the Global Head of Research of Rayliant Global Advisors. Phillip conducts research in support of Rayliant’s products, with a focus on quantitative approaches to asset allocation and return predictability within asset classes, as well as the design of equity strategies tailored to emerging markets, including Chinese A shares. Prior to joining Rayliant, Phillip was an assistant professor of Finance at the State University of New York in Buffalo, where he pursued research on quantitative trading strategies and investor behaviour, and taught investment management. Before that, he worked as a research analyst covering alternative investments for Hammond Associates, an institutional fund consultant. Phillip received a BA in economics and a BSBA in finance and accounting from Washington University in St. Louis, and earned his Ph.D. in finance from UCLA, where his research focused on the portfolio holdings and trading activity of mutual fund managers and activist investors. Premia CSI Caixin China New Economy ETF and Premia CSI Caixin China Bedrock Economy ETF track the CSI Caixin Rayliant New Economic Engine Index and CSI Caixin Rayliant Bedrock Economy Index respectively.