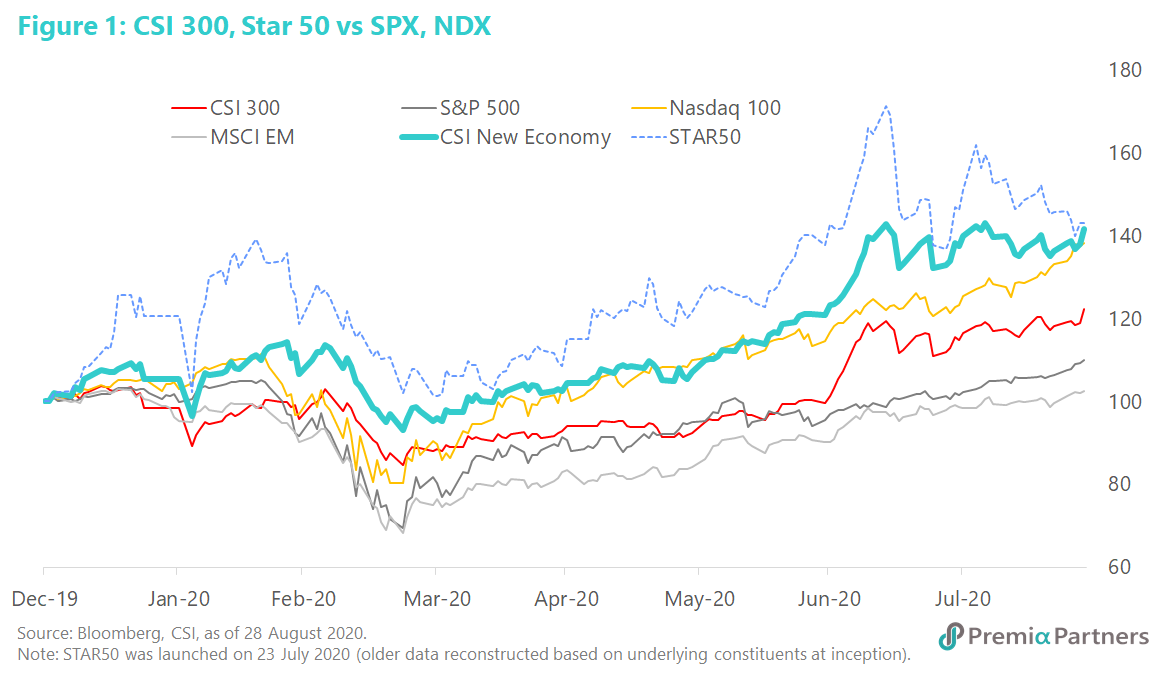

If we reconstruct the STAR 50 index that was launched on July 23rd by its constituents to the beginning of 2020, it has outpaced even the Nasdaq 100. More broadly, the CSI 300 has left the S&P 500 way behind – with the broad Chinese market index up 18% YTD against the S&P 500’s 8% gain (figure 1).

3173 HK, the Premia CSI Caixin China New Economy HKD ETF – which captures more diversified exposures to themes such as technological advancement, urbanisation, the rising middle class, growth of consumerism, education, the ageing of the population and healthcare – outperformed the CSI 300.

Geopolitical and pandemic challenges as megatrend accelerants. This outperformance in the midst of tremendous trade and tech pressure on China might seem counter-intuitive. It speaks to the megatrends that the trade-tech war and the COVID-19 pandemic have accelerated: 1) the push to increase the domestic consumption contribution to China’s GDP; 2) China’s pursuit of higher value-added production to support the higher wages needed for consumption growth and reduction of dependence on infrastructure investment; 3) the national push to develop Chinese technological independence; 4) more local sourcing of IT products within China; 5) the acceleration of digitization in China as a result of the pandemic.

The trade war and the push to grow domestic consumption’s contribution to China’s GDP. Household consumption had fallen from 72% in 1962 to a low of around 34% in 2010. So, China consumed less and less of what it produced over that time, exporting more and more of the GDP. As a result, it depended greatly on net exports and investments to drive GDP growth. They have now become economic and geopolitical vulnerabilities.

Economically, this has resulted in declining returns on investments and higher levels of credit for each unit of GDP growth. Geopolitically, its dependence on export markets exposes it to external pressure on even matters of internal policy – e.g. the United States’ demand for domestic economic policy changes as a pre-condition for trade.

Beijing’s recently articulated “double circulation” strategy – boosting the internal economy whilst maintaining the external – appears aimed at addressing these twin vulnerabilities.

Nonetheless, that shift in the composition of GDP was already happening anyway, even before the trade war erupted. China had lifted the household consumption share of GDP from 34% in 2010 to 39% in 2019. So, the trade war with the US may be an accelerant for necessary restructuring that was already occurring anyway.

Assuming a modest shift in the household consumption expenditure share of GDP from 39% to 45% by the early 2030s, the Chinese consumer market could be worth US$6 trillion to US$7 trillion more per year by early 2030s. That “delta” in Chinese consumer spending alone would probably be worth more than the entire Japanese GDP in year 2033.

The push to grow the household consumption share of GDP will likely see a lot more investment to boost productivity and wages. The argument against the “dual circulation” strategy goes along these lines: More consumption requires higher wages which would then undermine exports needed to maintain the “external circulation”.

Yet, Chinese average wages have been growing at around 8-10% per annum in recent years. That compares to 3-4% per year for the US, and around 1% per annum for Germany and Japan.

Further, the argument that higher wages undermine the “external circulation” is only true if it is assumed that exports remain at static levels of value-add.

China’s productivity growth averaged 15.5% from 1995 to 2013, but slowed to an average of 5.7% from 2014 to 2018. That is still high compared to 1-plus per cent for Japan and the United States. But yes, the US and Japan are working off much higher GDP per capita bases. China needs to reverse the productivity growth decline and we can expect a lot more investment and policy support for industries to climb the technological and value-add ladder.

US semiconductor bans have triggered a drive for technological self-sufficiency in China. By cutting Huawei off from supply of semiconductors, the US has stung China into urgent action to achieve technological self-sufficiency.

Last year, China’s demand for integrated circuits was valued at US$125 billion but it only produced US$19.5 billion, or 15.6%. The Government is targeting 70% self-sufficiency by 2025.

That’s a very ambitious target and would require a massive national effort. So, money is flowing in. Last year, the Chinese Government established a US$30 billion national semiconductor fund. This is further to the one set up in 2014. Private sector money has since followed into both venture capital and stock market investments.

From Just-In-Time to Just-In-Case with more local sourcing of IT and other restricted products within China and outside. This is not just about “patriotic buying”. One of the likely consequences of the US strategy of cutting China off from dealings with American companies will be to drive Chinese consumers to local alternatives. We could also see more American companies like Tesla expanding their local presence in China to be where their customers and highest growth market are. We could also see Chinese companies expanding their manufacturing and procurement presence in their key markets for the same logic – like Xiaomi in India.

If, for example, the US government bans Apple from dealings with WeChat even within China, that may mean Chinese consumers cannot download the app. WeChat, which is not just a messaging app but also a payments platform, is regarded as indispensable in China.

As the US prohibits dealings with more Chinese-owned apps – another example here is ByteDance’s TikTok – the end result could be a bonanza for Huawei’s domestic smartphone sales.

According to press reports, online business platform Xueqiu asked the public recently to choose between WeChat and Apple, if WeChat was banned from Apple’s app store. 800,900 out of 850,000 said they would switch to an Android phone. That is, they will walk away from Apple.

Apple’s share of the Chinese smartphone market had already fallen from 14% in 4Q19 to 8% in 2Q20. Huawei’s share picked up from 35% to 46% over the same period.

The pandemic has accelerated digitization in China. COVID-19 has not just accelerated digitization of business-to-consumer (B2C) applications and channels. It has also spurred the same in the traditionally less digitized business-to-business (B2B) space, according to McKinsey & Co.

“Before COVID-19, China was already a digital leader in consumer-facing areas—accounting for 45 percent of global e-commerce transactions while mobile payments penetration was three times higher than that of the United States,” said the May 2020 McKinsey report.

“Consumers and businesses in China have accelerated their use of digital technologies as a result of COVID-19. Based on our mobile surveys of Chinese consumers, about 55 percent are likely to continue buying more groceries online after the peak of the crisis. Nike’s first-quarter digital sales in China increased 30 percent year-over-year after the company launched home workouts via its mobile app, while property platform Beike said agent-facilitated property viewings on its virtual reality showroom in February increased by almost 35 times compared with the previous month.

“Working practices also changed significantly: enterprise communication platform DingTalk almost doubled its monthly active users in a single quarter to 177 million.

“In healthcare, digital interactions accelerated—the rapid growth of online consultations, partly thanks to a regulatory shift in reimbursement policy, as well as broader virtual interactions between pharmaceutical sales agents and physicians. These changes occurred ahead of wide deployment of 5G technology, which will likely catalyze the use of digital tools.”