The news flow from China and around the world about the spread of the so-called Novel Corona Virus (2019-nCOV) is not good.

Chinese equities have fallen sharply and other markets look wobbly – but what happens after the initial correction? Markets have reacted. The Shanghai Composite Index has fallen 5.5% from its January 14 high to its January 23 low. The Hang Seng Index has fallen 4.8% from its January 20 high to its January 24 day-low. The S&P 500 is sending technical signals of a rolling over from its late January high. But what about after the initial declines?

The great unknown – how long it will take 2019-nCOV to run its course. We do not know how long it will take to contain this – whether this will be as bad as SARS of 2002-2003, or worse? But the experts are worried. President Xi Jinping has just warned the situation was “grave”.

If it runs the course of SARS, this pandemic will take something like eight months before it burns itself out. SARS started in November 2002 and was officially declared contained by the World Health Organisation in July 2003. Could it be worse? This is the great unknown.

But we do know that markets are very forward looking and are not driven by human suffering. This is a statement of historical observation, not a moral judgment. Looking at historical events from pandemics to natural disasters to wars, it is observable that stock markets are not driven by human suffering, however great, however tragic. And they are very forward looking. To be clear, I am not trivialising the human cost of epidemics/pandemics nor the severity of this one. I’m simply looking at this through the lens of history.

The Dow Jones bottomed shortly after Pearl Harbour – when the conflict became a World War. During the Second World War, the Dow Jones bottomed on April 28, 1942. That was less than five months after Japan attacked Pearl Harbour. That is, the conflict became a World War, drawing in the United States. There are many theories about why the Dow Jones rallied (albeit with a few corrections in between) until mid-1946, after which it collapsed – after the War.

My interpretation is the market looked past the terrible human suffering of the war and saw the eventual defeat of Germany and Japan. The US destroyed the Japanese Imperial Navy in the Battle of Midway in June 1942 – a defeat Japan could not recover from. In the second half of 1942-early 1943, Germany suffered a devastating defeat at the Battle of Stalingrad, suffering losses it too could not recover from.

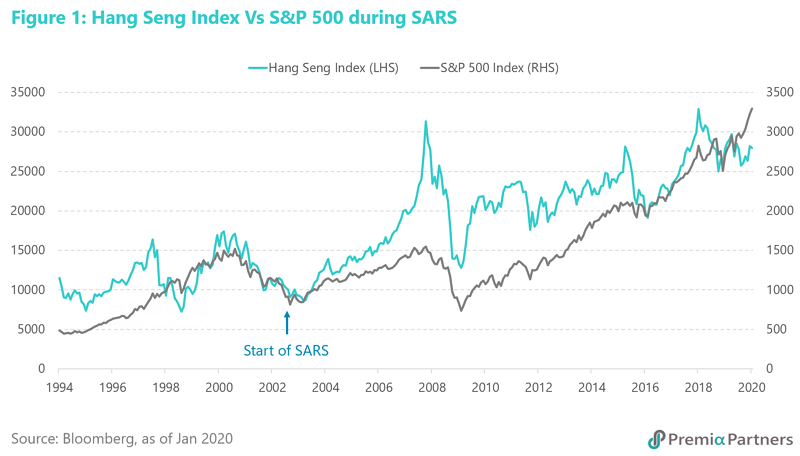

SARS, November 2002-July 2003, didn’t show a discernible impact on even the Hong Kong market. Now to epidemics and pandemics: What happened during the SARS epidemic in 2002-2003? The Hang Seng Index had already been in retreat – under pressure from bearish global market forces related to the Nasdaq Crash – from March 2000.

The first case of SARS was identified in Guangdong mid-November 2002. But in October 2002, the Hang Seng had already put in an intra-month low at 8773. And at the height of the epidemic – and it is important to note that HK had the second highest number of cases and fatalities in the world, next to mainland China – the Hang Seng only lost another 5% to the low in April 2003. But during the course of SARS, the Hang Seng Index actually picked up 9%, from its November 2002 month-low to its July 2003 high. Indeed, looking at the Hang Seng chart overlaid against the S&P 500, it becomes apparent that SARS was not a significant driver of the Hong Kong stock market over the medium-term. The movements of the Hang Seng largely mirrored those on the S&P 500. (Figure 1)

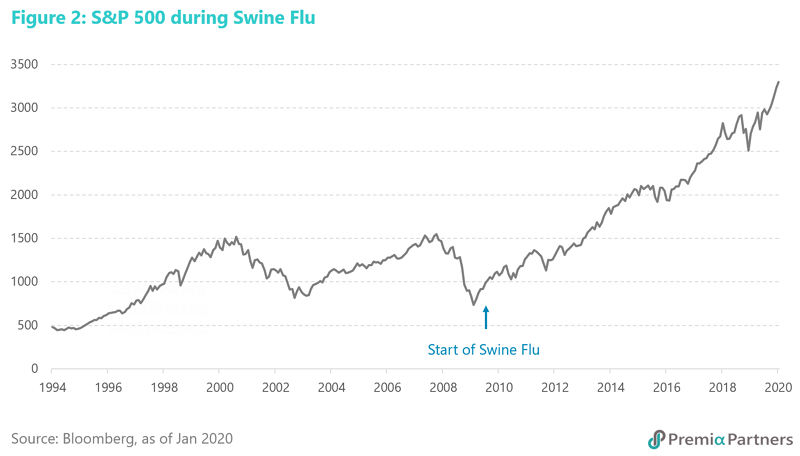

Swine Flu, April 2009-August 2010, did nothing to stop the market’s recovery from the global financial crisis. The S&P 500 barely skipped a beat in its ascent from the post global financial crisis low of March 2009, even though the US CDC estimated the pandemic caused anything between 151,700-575,400 deaths worldwide, compared to around 800 for SARS. The pandemic started in April 2009 and was declared by the World Health Organisation to be over in August 2010.

The S&P 500 picked up 30% from its April 2009 low to its August 2010 high (Figure 2). Belgium was the worst affected country. But the Bel20 index also picked up 30%. Indeed, both the S&P 500 and the Bel20 started to wobble mid-2010, long after the number of cases had declined significantly.

Just as the market paid little attention to the Swine Flu on the rise, it paid little attention to it on the decline. By mid-2010, the market was focusing on the Euro Area debt crisis, not the recovery from Swine Flu. It didn’t pay much attention to the H1N1 when it was rampant anyway.

Spanish Flu, January 1918-December 1920, again didn’t register significantly on the Dow Jones Index. This pandemic was so widespread the estimates of the death toll is still sketchy today. It is estimated at anything between 50 million to 100 million.

Yet, the Dow Jones rallied through much of 1918, correcting a bit only in late 1918, pushing yet higher through most of 1919, collapsing in late 1919, when the number of deaths per thousand had fallen dramatically. But that had little to do with the Spanish Flu.

The decline in the Dow Jones by late 1919 was a forward-looking response to the severe, 18-month deflationary recession that started January 1920, lasting to July 1921, during which the US GDP contracted 6.9%.

Markets look forward – and almost always at economics and money. The bottom line is that epidemics/pandemics and even natural disasters tend not change underlying trends in markets. If they were bullish before the epidemic/pandemic or natural disaster, the events may pause the market’s ascent, but generally not derail it. If the underlying trend in the market was bearish, the events tended to accelerate the downside. They generally don’t create the bearishness to begin with.

What about the situation today? The starting point should be what your underlying view of the market was before December last year. For me, the US market looked overvalued, technically “toppish”, and vulnerable. The market will use this as an excuse – as good as any – to correct an overvalued situation. However, absent a financial crisis – which was unlikely late last year and is still unlikely at this time, coronavirus or no coronavirus – a deep bear market is not a high probability risk.

Chinese equities were undervalued – particularly relative to developed markets. And Chinese equities have been in a gently rising channel since middle of last year. By early January, the Shanghai Composite was already at the top of its channel with oscillators signalling an imminent mean reversion. 2019-nCOV has simply accelerated that. Beyond that, the markets will be more interested in the economy than in the virus per se.

The SARS virus of 2002-2003 slowed the Chinese economy from 11.1% y/y growth in 1Q2003 to 9.1% y/y growth in 2Q2003. But the Chinese economy ended 2003 with 10% y/y growth, compared to 9.1% for 2002. If 2019-nCOV runs approximately the same course as SARS 2002-2003, we will likely see GDP growth declining in 1Q2020, recovering later in the year. And markets will likely resume their prior trajectories.

Meanwhile, on a personal note, to all our clients and friends, please take the necessary precautions, and stay safe.